Excerpt from The Australian Financial Review

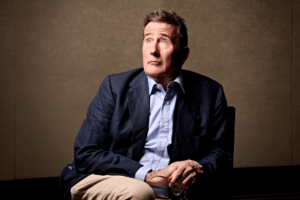

By Julie-anne Sprague

Rich List editor

The entrepreneur and corporate adviser has had plenty of woulda, shoulda, coulda moments. One of them cost him about $100 million.

It was about four years ago when Mark Carnegie could have backed himself in. He’d been wondering about all the hype surrounding cryptocurrency.

He’d come across ethereum, digital infrastructure that would allow for digital transactions underpinned by its tokens, ether. At the time one coin was worth about $200. By the end of 2021, it was worth $6000. While the price has since halved, had Carnegie backed himself, he thinks he could have made $100 million.

“Our big mistakes are mistakes of omission rather than commission because the worst thing that happens is you take a moderate amount of money, and you lose it,” Carnegie tells The Australian Financial Review’s How I Made It podcast.

Carnegie, who wanted to be like oceanographer Jacques Cousteau until he decided he wasn’t smart enough, studied law. “Increasingly, these days, there is just more and more and more time stuck fighting lawyers,” he says.

“If you don’t have some framework of understanding, you put your head in their hands every single day, and it just ends up in all sorts of a mess. Whereas if you’ve got some broad understanding, and I wouldn’t claim anything better than that, it’s been very, very helpful in my career.”

His dad, Roderick Carnegie, led the Australian arm of McKinsey before helming CRA Limited (now Rio Tinto).

He acknowledges his privileged upbringing. But, while born with a silver spoon in his mouth, he, for whatever reason, says he also has a chip on his shoulder.

Carnegie set up boutique advisory Carnegie Wylie with investment banker John Wylie in 2000 before the pair sold it to US-based Lazard in 2007 for what Carnegie, with tongue in cheek, says was for “a couple of bucks”.

Asked if he should be on the Financial Review Rich List, which has a cut-off point north of $600 million, Carnegie says: “Absolutely not”.

He thinks some people get too hung up on making money. He argues most people need enough money to pay off their mortgage, have a decent holiday and to be able to look after the health and welfare of their parents. And for the kids? Well, he says, it’s as the old saying goes: enough so they can do everything, but not enough they can do nothing.

“Beyond that, what do you need it for?” he asks.

Carnegie has seen the differences between business builders. And there’s a big difference between entrepreneurs such as Gerry Harvey, where making money is a little like playing competitive football, and others.

“It energises him. He was a better businessman at 70 than he was at 60. But he always had a talent. His life loses nothing for the fact that he spends his time doing that,” Carnegie says.

“Then [there are] other people who are absolutely about, ‘I want to make more than somebody else’. And you see them where the cortisol and the drug return is only when they’re betting everything on it. It’s that sort of crazy-eyes-roll-back-in-your-skull sort of person. So that’s a different bucket of person and you can see them, they’re driven by something deep and dark inside their soul, that ain’t ever going to quit.”

That doesn’t mean you don’t invest with that type of entrepreneur, he says. It does mean you need to keep a more careful eye on the exit.

“You’ve got to just find some way to come up with an effective dismount. It’s especially the case in financial businesses, where time and time and time again, somebody in a financial business just stays on way beyond when they should. You need to learn how to get off that train.”

He tells the podcast, one of the reasons he believes in cryptocurrencies is that in time content creators will want better compensation rather than give it all up to what he calls the “algorithmic overlords” such as Google, Meta and Apple.

“They control an unbelievable amount of economic activity and create these choke points in capitalism that mean that the economic rents go to the very small group of monopolists. And people seem to be OK with that, for reasons that absolutely dumbfound me.

“What I think crypto does at the broadest sense, is provide some levers for creators and the people who are actually providing content and participating in the attention economy to take power back from the centralised people.”

But crypto has its issues. He concedes it got its fair share of grifters and scumbags (Carnegie has previously said his personal investment fund lost about $100,000 in the collapse of the FTX crypto exchange) but he believes ultimately crypto is going to be a force for good.

“I’m a believer, philosophically, that crypto is going to be good. It’s going to be societally productive.”

Learn more about our funds at mhcdigitalgroup.com